Through the Decades – The 1930s

The Austin Company’s California Office Enters the Field of Aviation

Just five months after the Wright Brothers’ historic Kitty Hawk flight, the Samuel Austin & Son Company was formed. The Company began to envision how it could serve the aviation industry and become a key partner in the future of manned flight.

By 1916, Austin was more than a quarter-century old and had offices established across the country (California in 1921). The Company had built a reputation for innovation and resourcefulness. Widely recognized as the Father of Design-Build, Austin was often called upon when clients wanted single-source responsibility for their large, complex, and logistically challenging projects— a differentiator that continues today.

Ten years after Austin’s first project in the field of aviation with multiple major projects completed across the country for companies like Curtis Aeroplane and Boeing, it was time for the state of California to join the rapidly growing trend of commercial flight.

The Kelly Air Mail Act (1926) and the Air Commerce Act (1927) encouraged private investment in aviation, as did the 1926 establishment of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics. The growing enthusiasm for aviation prompted the Aeronautics Board of the U.S. Department of Commerce to conduct a survey identifying new airfield locations. The Aeronautics Board reported that Burbank had the most favorable airport location surveyed. In 1929, with the support of the Burbank Chamber of Commerce, United Aircraft and Transportation Company hired The Austin Company to begin construction on Los Angeles’ new airport located in Burbank. Occupying approximately 234 acres of land, the airport boasted more paved landing area than any airfield at the time. An article featured in Airports Magazine the following year (1930), reported on the construction effort, and described the scale of the endeavor in relation to the necessary modifications to the landscape, stating: “Over one hundred large oak trees were removed from the field and from property adjoining the field, by arrangements with the owners, to eliminate every possible hazard.”

The Terminal Building included administrative offices, ticket offices, a baggage room, a telegraph office, and other conveniences. The airfield’s layout was carefully planned, locating public structures like the Terminal Building near the southeast corner of the field, separate from the property’s industrial, support, and private facilities.

Austin was also responsible for constructing Hangar 1 and Hangar 2.

Memorial Day weekend, 1930, marked the opening of the world’s first million-dollar airport. Airplane races and a staged air battle with military bombers and fighter planes entertained the crowds on the ground below. As the author E. Caswell Perry relates in his book entitled Burbank: An Illustrated History, the opening day event drew large crowds eager to participate in the festivities. He writes of the event, “More than 25,000 automobiles jammed the new airport facilities, and the overflow crowds included many of neighboring Hollywood’s brightest movie stars.” Only Pacific Air Transport (later acquired by United Airlines) operated from the airfield at first. Still, the scale of operations at the new airport expanded quickly, as Perry also describes, writing as follows, “By 1933, when the airport was renamed Union Air Terminal, it had become the primary facility for the greater Los Angeles area, used by all the major airlines of the day.”

The Terminal Building was initially named United Airport. From 1935 until 1940, United Airlines assumed control of the Burbank airfield. Several major airlines began operating from Union Air Terminal during that time, including Pan American, Western Airlines, and Trans-World Airlines. In early 1939, American Airlines also operated out of the Terminal Building. This made the Union Air Terminal the center of all primary airline operations in the Los Angeles area. The decade of the 1930s was a historic one for the Burbank airfield. The field welcomed aviation pioneers like Howard Hughes, Amelia Earhart, Wiley Post, and Charles Lindbergh.

In 1940, the Airport property was sold to a neighboring company, Lockheed Aircraft—a company that Austin serves to this day—which continued to operate the Terminal Building—supporting passenger and airfreight operations—while also utilizing the airfield to manufacture and test new aircraft.

Austin’s California Office Enters the Field of Radio with NBC Radio City West

Radio was one of the few industries to grow during the Depression. It was the mid-1930s and the competing networks of CBS and NBC were building for much-needed space as well as for prestige.

Experimental radio broadcasting began in 1910. KDKA, a station out of Pittsburgh, PA, broadcasted the 1920 presidential election results on November 2, 1920. This event is considered the beginning of professional broadcasting. Seven years latter stations WJZ and WEAF would merge to create NBC and the race to build bigger and better studios began.

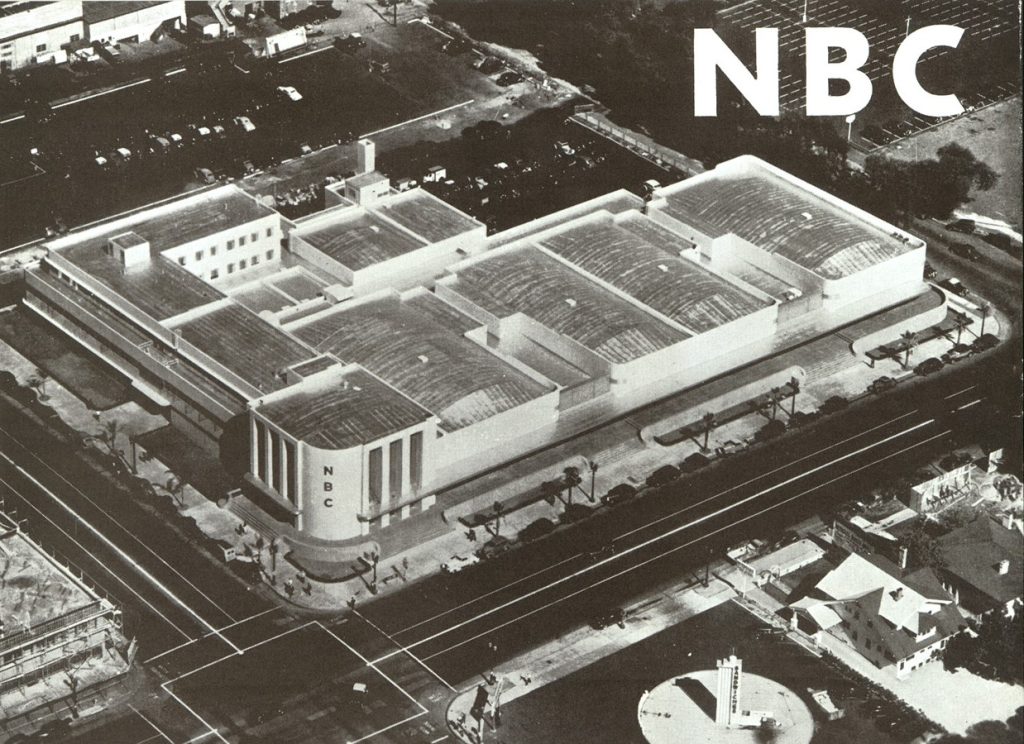

CBS engaged renowned architect William Lescaze to design its Hollywood studios. Only a block away, on a site at Sunset and Vine, NBC relied on The Austin Company to design, engineer, and build its new studios. When completed in 1938, NBC’s Radio City of the West stood as an American architectural masterpiece. Its design was pure, striking and thoroughly functional— a style pioneered through Austin prototype models displayed in early issues of Fortune magazine.

For its new Hollywood Studio, NBC, and Austin architects and engineers had a clean slate. Former radio broadcasting operations had not been so easy, having utilized existing office building space, often on a second floor, and fitting complex broadcast equipment into a space ill-designed to support it. With this project, the premier of an ideal arrangement would be achieved, with ample space on the ground level.

Four auditorium studios, each planned for an audience of 350 guests, were located to give public access from Sunset Boulevard. Radio talent and operating staff were well-screened from the public in their own circulation corridors, even to the extent of private auto drive entrances and parking. Along one end of the five-acre site, on Vine Street, a three-story office wing provided space for executive and administrative functions.

Sound, the soul of a broadcasting facility, can also be its greatest enemy. Vibration and sound conductivity were addressed in the design, engineering, and construction, including separate foundations for the auditoriums.

The facility housed a total of eight studios, four of which accommodated studio audiences. Each was supported on a separate sound-isolating foundation and served by an independent air conditioning system to prevent noise from passing through the ductwork. Soundproofing was said to be so complete that a truck could have rumbled down the central corridor without transferring vibrations to adjacent studios. An NBC spokesman called NBC Radio City West “the ideal facility for broadcasting!”

Austin went on to design and build for all three major networks. And, in the early 1940s, Austin invested its own research and development to develop models for prototype TV studios. The conversion of NBC Radio City West for television being among the first.

We will talk about this further next month as we look back at the 1940’s.

|

KEN STONEVice President and Project ExecutiveCall 949.451.9009 | Email Ken | View Profile |